NASA adds funding to Blue Origin and Voyager Space commercial space station agreements

TITUSVILLE, Fla. — NASA has added milestones and funding to agreements with two companies working on commercial space station concepts using money from a third agreement that ended last year.

NASA announced Jan. 5 that it added a combined $99.5 million in funding to existing Space Act Agreements with Blue Origin and Voyager Space. The two companies received the original agreements in December 2021 as part of NASA’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations, or CLD, program to spur development of commercial space stations intended to succeed the International Space Station.

Blue Origin, which is developing the Orbital Reef space station with Sierra Space and other companies, received an increase of $42 million to its original $130 million award. The increase includes additional milestones for subsystem design reviews and technology maturation, as well as work on the station’s life support systems.

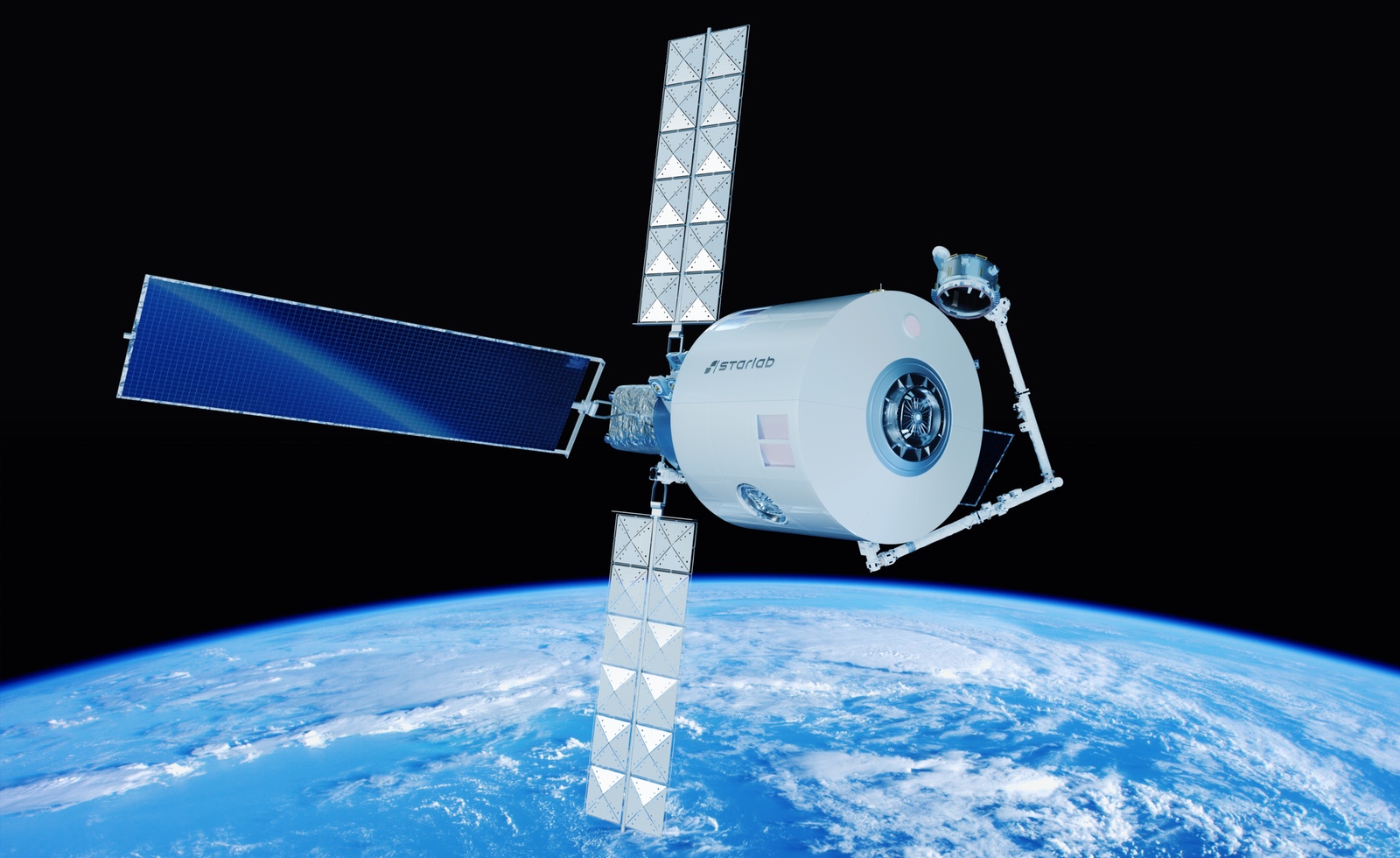

Voyager Space, which is partnered with Airbus Defence and Space to develop the Starlab station, received $57.5 million in additional funding on its $160 million award. That will go towards various development milestones for the station as well as work to upgrade Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus cargo spacecraft to enable it to dock directly with the station rather than be berthed to it by a robotic arm.

“The milestones target key technology and risk reduction areas of our partners’ designs,” said Phil McAlister, director of commercial space at NASA Headquarters, in a statement about the revised agreements. “The milestones also include additional hardware testing, which is critically important to any spaceflight development effort.”

The funding comes primarily from a third CLD agreement that NASA awarded to Northrop Grumman. Northrop announced in October that it would no longer pursue its own space station but instead would work with Voyager Space on Starlab, including providing a version of Cygnus to transport cargo to Starlab.

As part of that partnership, Northrop withdrew from its NASA CLD agreement. The agency stated in October it planned to reallocate the $89 million that had not been spent by Northrop on its $125.6 million award to other CLD providers. NASA said in the Jan. 5 announcement it combined that unused money with “other program funding” to reach the $99.5 million it added to the Blue Origin and Voyager Space agreements.

NASA is also in discussions with Axiom Space, which has a separate contract with NASA to access a docking port on the ISS for commercial modules that will form the basis of a future standalone commercial space station. NASA said it is negotiating “additional content” for that contract with Axiom, details of which are still being finalized.

The agreements with Axiom Space, Blue Origin and Voyager Space are all part of NASA’s strategy to support the development of commercial stations the agency wants to have in operation by late this decade to support a transition from the ISS, set for retirement in 2030. NASA would then be a customer of those commercial stations along with other space agencies and companies.

“The agency is committed to continuing to work with industry with the goal having one or more stations in orbit to ensure competition, lower costs and meet the demand of NASA and other customers,” Angela Hart, manager of the CLD program at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, said in the statement.

There continue to be concerns, though, about the ability of companies to develop commercial space stations by the end of the decade. At a NASA advisory committee meeting Nov. 20, McAlister acknowledged the possibility of a short-term gap between the ISS and commercial stations if those commercial stations are not ready by the end of the decade and the ISS is not extended.

“A gap would not be great,” he said at that meeting, “but I also don’t think it would be unrecoverable, either, especially if it was relatively short term.”

Hart, at the same meeting, said it is difficult to estimate now the probability that at least one commercial station will be ready in time. The agency may not have a better grasp of those companies’ abilities to meet their schedules until after NASA issues what it calls Phase 2 contracts in 2026 to certify the stations for use by NASA astronauts and to purchase services.

“That first six months to a year, once that contract is awarded, is where I think we’ll have the best understanding of what our schedule is,” she said.

Related

ncG1vNJzZmiroJawprrEsKpnm5%2BifK%2Bt0ppkmpyUqHqnwc2doKefXam8bq7Lrpxmp6KetKq6jJqlnWWmpMais8SrZKyokZiybq%2FOpqSeqpOerq150qmYnJ1dqMGiwMiopWaZl6eyprnEp6usZw%3D%3D